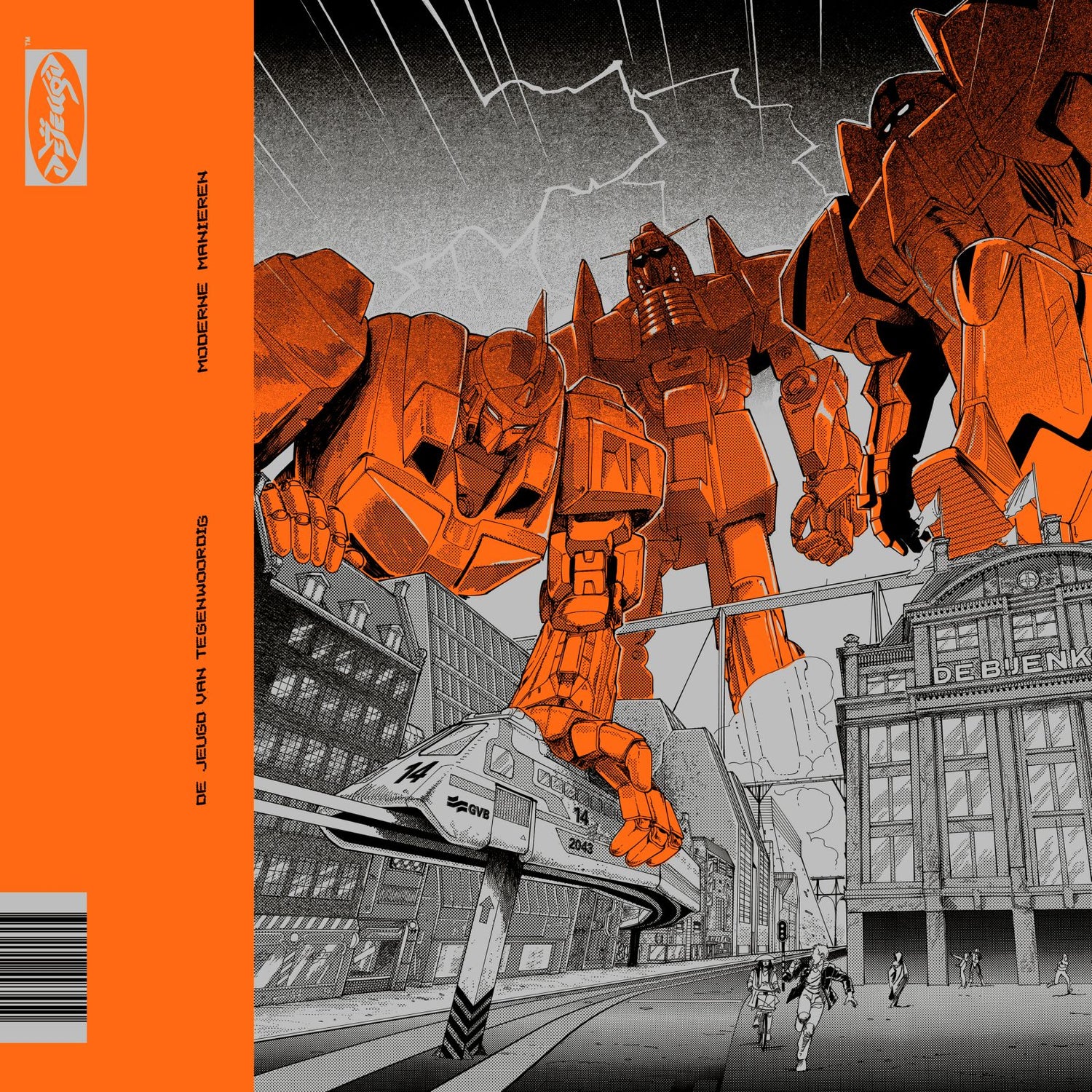

Moaners sometimes moan about the lack of excitement in post-war Dutch culture. Well, look, that certainly does not apply to the Utrecht punk scene of four decades ago, because, my goodness, what a lively and tumultuous event that was! Let's see, who did you have again? You had: the Lullabies, the Nixe, Pitfall, the Rapers, Bizon Kidz, Transgressorz, the Cavias, Coitus Int, Anthrax, Noxious, Blitzkrieg, Pin-Offs, Know-vibbs, the Duds, Scrambled Eric, Rakketax, the Wogs, the Clits, ZeroZero, God, 700 Enemies, Dangerous Pyamas, Rabies, Local Negatives, Disorder, Hi-Jinx, Dadaguluks, De Megafoons, Cold War Embryos... The list seemed endless and I'm sure I'm forgetting a few. I will also conveniently remain silent about everything that would come after that. But eh… the Utreg Punx, in what sense did we progress with that? To the outside world it was mainly an angry army of non-musicians. What did they bring us in the end?

Local city marketers, columnists, imported professional managers and other hipsters are quick to use the term 'Utreg' these days, indicating that they consider themselves so well-versed in their city of residence that it gives them the privilege of using this nickname. How different things were in the mid-70s. 'Utreg' was then only found on hastily painted banners in the Galgenwaard stadium. And in the Galgenwaard there was always a fight. You know, from the golden age when the riot police still stormed the Bunnikside on horseback and armed with a long stick... People with a bit of education or culture in their ass avoided the Galgenwaard like the plague. After all, the dividing line between high and low culture was still very strict. It was the merit of a number of punks that they took the term 'Utreg' from the stadium into the culture, and in doing so perhaps made local culture a little more accessible. In any case: the term 'Utreg Punx' was born, a compilation EP from 1980 proudly bore that title for the first time.

In an old interview with the Utrechts Nieuwsblad, Merlin, singer of the Duds (pretty much Utrecht's first punk band) tries to characterize himself. With undisguised pride he declares: 'I demolished everything. Ashtrays, jukeboxes, pinball machines and drum sets. Did you just hear that glass falling at that pinball machine?' Yep, deeply embedded in the Utrecht psyche is that irrepressible urge for skilled deconstruction. It all started in 1577 with Trijn van Leemput, a local heroine who led a wild mob. They managed to completely destroy the music palace Vredenburg, or something like that, in no time. Another highlight (we easily switch between centuries) was the single-handed and spontaneous demolition of the old Galgenwaard stadium in 1981, TV images of which went around the world. A real popular party broke out and the Utreg Punx also showed their worth. Yes, in essence, demolition is a creative act of course and I think it has something poetic about it. That the general public uses the term 'vandalism' for this is only secondary, it says at most something about their own narrow-minded worldview.

The punx also had their own interpretation of the concept of mobility. They often went in groups by train or by bus(es) to places like Babylon in Woerden, Kaasee (Kreatief Centrum) in Rotterdam, Drieluik in Zaandam, Parkhof in Alkmaar, various squats in Mokum or to Simplon in Groningen. Demandingness played no role in this. Twenty men crammed into such a bus was never a problem, not even if the bottom of such a rented brig was already half rusted through. And if it came to fights in such places, then some back-up from within was always useful and practical. The book 'Doornroosje, 20 jaar Jongerencentrum' (Doornroosje, 20 years of Youth Center) nicely points this out: 'Complete invasions of bands and their supporters take place from Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Utrecht and abroad. Memorable evenings.'

Many of the punk bands soon started to self-release 7 inches. Unhindered by any knowledge of matters such as marketing, price structure, margins or VAT, they placed a strong emphasis on what is known in retail as 'vertical price fixing'. The sleeve would always have something like 'don't pay more than 3 guilders' printed on it, with which the punks explicitly imposed their will on the retailers. The poor shopkeeper who then bought such a record (for a purchase price of about 2.75 guilders) earned almost nothing from it, and if he got it into his stupid head to add a few quarters on top, he ran the risk of getting a brick through his shop window in the middle of the night. Because, well, if there was one thing punks hated, it was fucking commerce! The fact that those same records now sometimes fetch a few hundred euros on Discogs and, oh the irony, are cherished items in the hands of those same old punks, is irrelevant.

Never to be forgotten: the catalyst that got the whole local punk thing moving was the exciting concert that the Ramones (supporting act Talking Heads) gave in the spring of 1977 in RASA on the Pauwstraat. From then on, 'punk' was a concept, the aspiring punks had a clear example in mind, they understood how to hold a guitar and humanity started standing at concerts again for good instead of, as before, sitting on the floor in that stupid tailor's seat!

'The music did nothing but yapping furiously. There wasn't a shred of a tune.'

From 'The Wingerdrank' by F. Bordewijk.

Somewhere in the 80s/90s the idea must have taken hold that pop venues (and cinemas and theatres for that matter) should have a black painted interior, the term 'black box' originated at that time. Nowadays we don't know any better, the blacker a venue is painted the better the stage event comes into its own, we think. But this was not at all self-evident until the early 80s. Only Paradiso has remained virgin white on the inside to this day. Since many punks at that time were as it were born with a fat Edding felt-tip pen or spray paint can (two great innovative products at that time) in their inside pocket, this turned out to be a typical case of tying the cat to the bacon. Many pop venues were soon scrawled from top to bottom with band names and slogans, 'destroy!, fuck fascism! Vonhoff is a pig!' This to the great displeasure of the old hippies who were in charge. The term 'graffiti' was not yet common at the time and it was the punks who popularized its use. And in passing gave those dirty hippies a final kick towards the exit...

Like other cities, Utrecht had a selection of punk fanzines (Duvel, Orgie, Vrot, Riezistuns) but strangely enough it was the bourgeois press that had the most impact on the scene. The Utrechts Nieuwsblad, once very bad during WWII, may have a knack for completely ignoring culture, but it was their pop writer Ron Blansjaar who proved to be a fervent advocate of the Utreg Punx. Blansjaar had consciously experienced the old days and saw clearly which way things should go. In the punx he saw, as it were, the proclaimers of a new gospel. He enthusiastically reviewed local bands, concerts and records, with which he provided the necessary impulses. At the same time he made short work of the old guard, which was not always appreciated.

With over 730 wharf cellars, bubbling in its guts for centuries, the city of Utrecht gave the punx a unique natural habitat. Many were the parties that took place in these dark caverns. However, the cellars were less suitable as a practice or performance location. Not only because the acoustics were makeshift with the vaulted spaces, but you also had to be careful that the high humidity did not cause amplifiers and guitars to be steadily, eh... demolished from the inside. The musty stench that could rise from the moldy brickwork also took your breath away, sometimes lingering in your clothes for days.

Above ground, too, the stage situation was crap, or even worse. After the Ramones, only a handful of punk bands of repute visited the old episcopal city (the Boys, Pure Hell, Only Ones, Flyin' Spiderz, The Cramps). The contrast with the situation in other cities was indigestible. In addition, around 1980 RASA started focusing on other genres, music café EigenWijs got into a fight with punk groups, the old wooden Tivoli temporary building on the Lepelenburg had been set on fire (the perpetrators also flew off) and a new music centre was built on the Vredenburg for 60 million ducats, but pop music would only be marginally represented there, as soon became clear. It was therefore logical that the cry from the heart ' we want punkkeet' appeared here and there on walls. But a goal without a plan is just a wish, the punks must have realised instinctively. An ad hoc alliance with the squat scene arose naturally and a series of notorious squatting actions followed, in which the Utreg Punx always led the way as brave warriors. Such a squat was usually for one evening, the target was an empty hall or building. On an improvised stage, some hastily assembled bands played.

A favourite target of criticism was Henk Vonhoff, mayor in the punk era (1976-1980). With his imposing stature he was a true regent, a liberal of the old school who did not tolerate any contradiction. 'Youth culture is fun but we are not going to spend money on it,' he is said to have grumbled once. My brother once came home with the story that during a squatting action of the (then newly opened) small hall of Vredenburg, Mr Vonhoff was personally present to provide the police with military advice. On his authority the hall was closed off and the heating turned up high (!). A few hours later the seriously sweaty occupiers were finally beaten out, with Vonhoff personally grabbing a few of those people by the scruff of their necks and dragging them outside. Talk about taking action!

Ultimately, the squatting actions would lead to a grand triumph. The old, vacant NV-House on the Oudegracht was jubilantly taken possession of after a few battles. 'The final battle' consisted of the cops barricading themselves downstairs in the hall in the company of a pack of hungry police dogs, while the activists had entered the hall via the balcony. The blues had not counted on the bottles of ammonia that the activists threw down. The rotten animals immediately started hallucinating, after which they wisely retreated with their owners and all, with their tails between their legs, no doubt. Soon after, the NV-House would be renamed Tivoli. Punk, post-punk and new wave music had finally found their landing place, hurray! Because De Vrije Vloer was also founded at the same time and Kikker and Muziekcentrum Vredenburg (still) did a lot of pop, Utrecht could finally compete with the big boys. A brilliant era full of memorable concerts began.

Which brings us back to our time. The punks of yesteryear have long since disappeared into anonymity, some of them now have a garden on their stomach. De Vrije Vloer eventually became known as De Helling, dB's, Ekko and ACU were added. Tivoli would grow into a (municipal forced) merger with MC Vredenburg and SJU Huis, with which 'music palace' TivoliVredenburg was born. Many an old punk likes to grumble about what they see as a megalomaniac prestige object and let's be honest, you can't really call it a punk club. But it is a concrete result of all the efforts and at least as important: their own children party there all the more happily. And you could see that as a reckoning with the old guard, as well as a circle that is complete. It doesn't get any cooler than that, right?

Jos de G.

The Chainsaw Blog

This record is dedicated to those who are no longer with us:

Rob van Asperen

Max Bosschaert

Babbi/Arnoud Brinkman

Peter Daniels

Joeri Elfrink

Nicole Holmes

Ollie ten Hoopen

Robin Meijerink

Heino l'Ortye

Edie Renes

Ferdie Tummers